Adorable Keepsakes Hummel figurines come from religious background

“Sister’s Children” limited edition figurine, created to celebrate Hummel’s 100th Anniversary, sold at auction for $3,750 in 2021. (Image courtesy of invaluable.com)

Jan/Feb 2026

Cover Story

Adorable Keepsakes

Hummel figurines come from religious background

by Corbin Crable

You might know someone who collects Hummel figurines – those figurines of cherubic children at play or dutifully marching off to school, satchel in hand. Or perhaps you’re a collector yourself, boasting a sizable group of figurines displayed prominently in an antique cabinet or on a bookshelf or table. You’re certainly not alone; those precious porcelain treasures have enjoyed a cultlike following for decades.

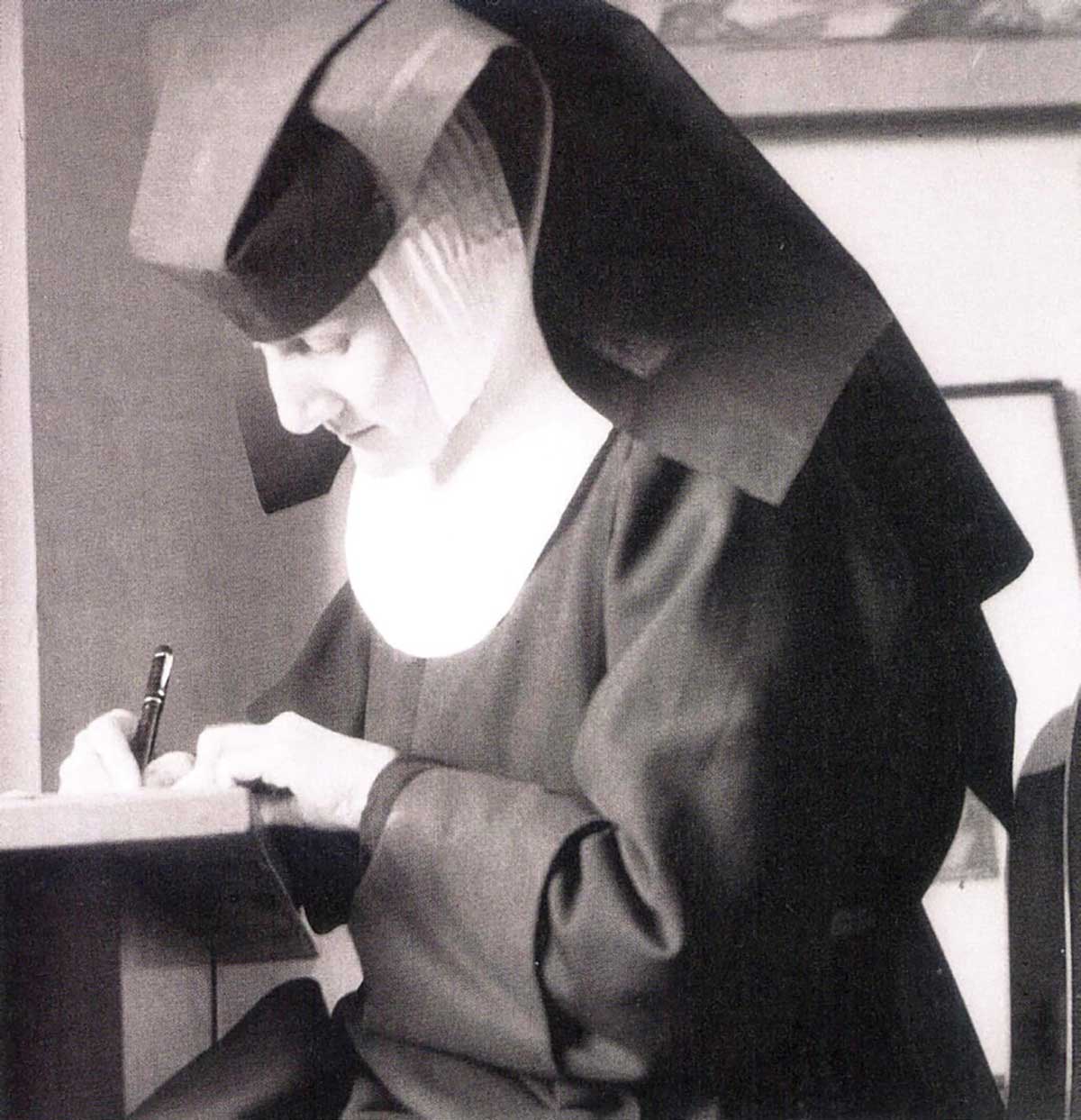

An idea created in a convent

The figurines come from the most humble of beginnings. Sister Maria Innocentia, born Berta Hummel in Bavaria in 1909, possessed an artistic talent from a young age. The young Berta would tap into her blossoming imagination to sketch and paint idyllic scenes on postcards. In 1927, she moved to nearby Munich, Germany, in order to fine-tune her talent; however, a higher calling from God would lead Berta to a convent in the early 1930s, where she would take the name Sister Maria Innocentia Hummel.

“Apple Tree Girl”

“Apple Tree Girl,” HUM 141, was designed in 1940. (Image courtesy of Antique Trader)

“Within the walls and the beautiful surroundings of the centuries-old convent, she created the paintings and drawings that were to make her famous. Within these sacred confines, her artistic desires enjoyed unbounded impetus,” according to a 2021 article by Hummel expert Heidi Ann von Recklinghausen in Antique Trader. “As she adjusted to convent life, Maria Innocentia found fulfillment in teaching art to kindergarteners and leading the convent’s Vestments Department, designing clerical robes, church altar cloths and banners. She also began to sketch the endearing pictures of children that would someday make her famous.”

The children depicted in Sister Innocentia’s drawings all shared a distinct look, helping her work stand out among others, von Recklinghausen writes.

“These were stylized images of country children going to school, making music, playing simple games. The colors were muted, the style loose and sketchy. And the children were enchanting. Cheeks were plump, hair windswept,” she writes. “Shoes were too big, and socks sagged. The artwork was published in a variety of forms, including postcards, and Sister Maria Innocentia Hummel began to develop a reputation as a fresh talent in the world of religious art.”

“Benjamin and Luisa”

“Benjamin and Luisa,” one of many figurines sold through Hummel’s website. This figurine is priced at $333. (Image courtesy of hummelgifts.com)

Hummel figurines take shape

Though Sister Innocentia died of tuberculosis in 1946, she would live to see the children depicted in her postcards come to life as figurines, all thanks to a German company that specialized in porcelain and fine earthenware. The company, W. Goebel Porzellanfabrik, had been founded in 1871. By the time he gained control of the company in 1929, the owner, Franz Goebel, had decades of experience in the industry, crafting a name for himself and his company throughout Europe. Goebel first learned of Sister Innocentia’s popular postcards in December 1933, and the Sisters at her convent asked Goebel himself to reproduce the cards in some form; Goebel decided they would be best created as a series of figurines.

From their introduction in 1935, the figures were a hit, and though production was paused throughout World War II, it quickly resumed immediately following the war.

“During the American Occupation, the United States Military Occupation Government allowed Goebel to resume operation. This included the production of Hummel figurines,” von Recklinghausen writes. “During this period, the figurines became quite popular among U.S. servicemen in the occupation forces, and upon their return to the United States, many brought them home as gifts. This activity engendered a new popularity for Hummel figurines.”

Schoolboy

“Schoolboy,” originally crafted in 1938. Each authentic Hummel figurine is made with a numbered mold; the mold number is also known as the HUM number. (Image courtesy of Antique Trader)

The Little Fiddler

“The Little Fiddler,” HUM2, was among the very first figurines created in 1935. (Image courtesy of Antique Trader)

Valentine Gift

Many figurines, such as the “Valentine Gift” were also featured on collectible plates. (Image courtesy of Antique Trader)

Adventurebound

The most valuable Hummel figurine is “Adventurebound,” created as a limited edition piece in 1957. Experts price the piece in pristine condition between $4,900 and around $10,000. (Image courtesy of littlethings.com)

Rising popularity, rising prices

Throughout the mid-20th century, Hummel figurines continued to climb in both price and popularity, with other items being produced bearing the Hummel name, including collectors plates. The figurines’ popularity reached its zenith in the 1970s as prices spiked. Limited special edition figurines have been produced since then, with the pieces becoming more intricate in design. Today, even 90 years after they first hit the market, all Hummel figurine designs must be approved by the leadership of Sister Innocentia’s convent.

Demand for Hummel figurines waned in the late 20th century, and the production company declared bankruptcy in 2017, axing the number of figurines produced annually from 55,000 to only 20,000.

Still, communities of collectors continue to keep their zeal for the figurines alive through both in-person and online groups, the most prominent being the company’s original M.I. Hummel Club. Museums paying tribute to the figurines have opened to the public as well. The Hummel family home – the birthplace of Sister Innocentia – is operated by her nephew. Meanwhile, the late Donald Stephens, a longtime mayor of Rosemont, IL, donated his extensive Hummel collection to a museum that would eventually bear his name.

“The unique Donald E. Stephens Museum of Hummels is the largest display of M.I. Hummels in the world. Here you can take a close look at more than 1,000 rare M.I. Hummel figurines and ANRI woodcarvings,” according to the City of Rosemont’s website. “The late Mayor shared his love of the figurines with millions of national and international Rosemont visitors. The establishment of the museum ensures not only that his collection will remain intact, but that it will continue to grow.”

Sister Maria Innocentia Hummel

Sister Maria Innocentia Hummel. (Image courtesy of hummelgifts.com)

Hummel dealer’s plaque

A Hummel dealer’s plaque, sold at auction for $2,100 in 2021. (Image courtesy of invaluable.com)

A mark of authenticity

Though original Hummels are plentiful, imitators still exist. To ensure yours is an authentic Hummel figurine, check for the trademarks. The original Crown Mark, for instance, was used in the earliest figures produced; it displays an image of a crown with the initials “WG” (for William Goebel) directly below it. An illustrated guide to this and other Hummel trademarks can be found at https://www.antiquetrader.com/collectibles/hummel-trademarks-identified.

In addition, according to Antique Trader, the signature “M.I. Hummel” at the base of the piece, along with a mold number, will both appear on authentic Hummels. Fake figurines will be missing those marks and lack detail in general.

Pricing for Hummels can vary significantly, but it is important to note that their value has declined over the years due to market saturation and decreasing popularity. Most are worth less than $100, but pieces that are both larger and rare, as well as those in perfect conditions with original box can fetch several thousand. It always helps to check sites such as eBay and Etsy – or one of the several Hummel price guides – for more specific numbers.

Of course, like so many other antique and vintage collectibles, Hummels’ value lies in their sentimentality or nostalgia, which is simply priceless.

“(Hummel figurines) have become symbols of carefree childhood – to the enjoyment of millions,” according to hummelgifts.com. “Collectors and admirers from all over the world agree that the artistic perfection and quality of an M.I. Hummel product are unique in the world.”

Trademark and Mold

Trademark and mold

Umbrella Kids

Umbrella Kids

Deck the halls with Hallmark Keepsakes help collectors make their season merry and bright

Hallmark’s Christmas offerings include more than ornaments for your tree. This tabletop decoration pays tribute to “A Charlie Brown Christmas,” which first aired in 1965. (Image courtesy of Hallmark.com)December 2025Cover StoryDeck the halls with Hallmark Keepsakes...

A salute to militaria Military collectibles preserve history of service to country

Examples of militaria from the Great War can be found at the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, MO. (Image courtesy of U.S. News and World Report Travel)November 2025Cover StoryA salute to militaria Military collectibles preserve history of...

Tales of the unknown Ghost stories still spook, delight us

Edgar Allan Poe, considered one of the writers who kicked off the golden age of ghost stories, penned many a terrifying tale in his time – including a short story called “The Black Cat,” in which a seemingly supernatural cat takes center stage as the narrator reels...

That nifty neon Neon signs brightly beckon our collective nostalgia

The interior of the American Sign Museum in Cincinnatti, OH. (Image courtesy of The American Sign Museum)September 2025Cover StoryThat nifty neon Neon signs brightly beckon our collective nostalgiaby Corbin Crable Petula Clark’s 1964 hit song “Downtown” made neon...

UP, UP AND AWAY Comic books’ popularity only growing in Digital Age

Nicknamed “The Big Blue Boy Scout,” DC Comics’ Superman is the gold standard for superheroes and the pursuit of good. (Image courtesy of Metaweb)August 2025Cover Story UP, UP AND AWAY Comic books' popularity only growing in Digital Ageby Corbin Crable The box office...

Swingin’ into Summer Stop and watch the world go by on a porch swing

If you’re looking to buy a porch swing on a budget, this retro model is available online for $195. (Image courtesy of The Porch Swing Co.)July 2025Cover StorySwingin’ into Summer Stop and watch the world go by on a porch swingby Corbin CrableThey’ve gone through...

The Heart of the Home Kitchen appliances reveal food prep, storage trends throughout the years

By the 1950s, refrigerators were able to accommodate the needs of the modern family, even keeping them cool when summer’s heat arrived. (Image courtesy of Pinterest)June 2025Cover StoryThe Heart of the Home Kitchen appliances reveal food prep, storage trends...

A nickel’s worth of fun Jukeboxes spin the tunes and create memories

A classic Wurlitzer 1015 model. Created in 1946, it is the biggest selling jukebox in history. (Image courtesy of The Men’s Cave)May 2025Cover Story"A nickel’s worth of fun" Jukeboxes spin the tunes and create memoriesby Corbin CrableThe jukebox remains one of the...

Molded meals Aspics inspired bizarre dishes, but rarely appetite

Apsics remain quite common in European cultures. For instance, this colorful shrimp and veggie aspic makes a delightful Italian lunch entree. (Image courtesy of La Cucina Italiana)April 2025Cover StoryMolded meals Aspics inspired bizarre dishes, but rarely appetiteby...

Do the Hustle! Disco made us boogie-woogie the night away in the ‘70s

The iconic mirror ball, setting the tone and delighting disco dancers for decades. (Image courtesy of dancepoise.com)March 2025Cover StoryDo the Hustle! Disco made us boogie-woogie the night away in the ‘70sby Corbin CrableThose who remember the bygone days of disco...