July 2022

ANTIQUE DETECTIVE

Commemorative collectibles depict historical events

by Anne Gilbert

Commemorative items for Collectors

The recent celebration of Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee has created many commemorative items for collectors. There are t-shirts, coffee mugs and cushion covers, to mention only a few.

Famous people from presidents to inventors and celebrities have been immortalized as collectible objects — George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and Martin Luther King Jr. among them.

Historical events from battles to Charles Lindbergh’s solo, nonstop transatlantic flight to actors and musical groups have been and are being made by limited editions companies such as The Bradford Exchange. While early examples are mostly in museums, many still come up at auctions. Who knows how many are awaiting your discovery?

Historically, commemorative and jubilee souvenir items go back several hundreds of years. European and American history used plates, figurines and a variety of ceramics and glass to display political and cultural events and causes.

The earliest British Jubilee commemorative item is a Delftware plate made late in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I in 1600. In 1680, a commemorative mug was made during the reign of Charles II.

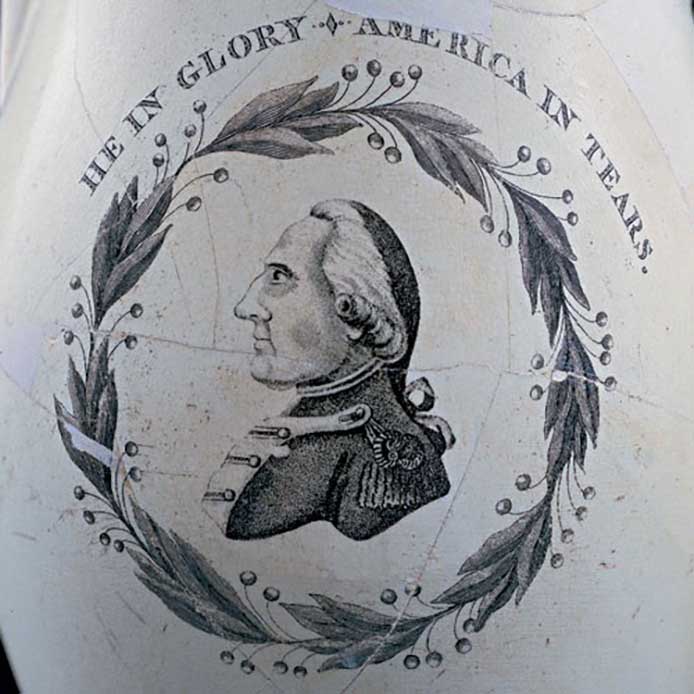

Developments in manufacturing techniques allowing images and designs to be transferred to pottery in the early 19th century were created in 1760. A Worcester pitcher was made commemorating the death of King George II. One side showed his likeness, the other one of his naval battles. A current price offering one is $9,000.

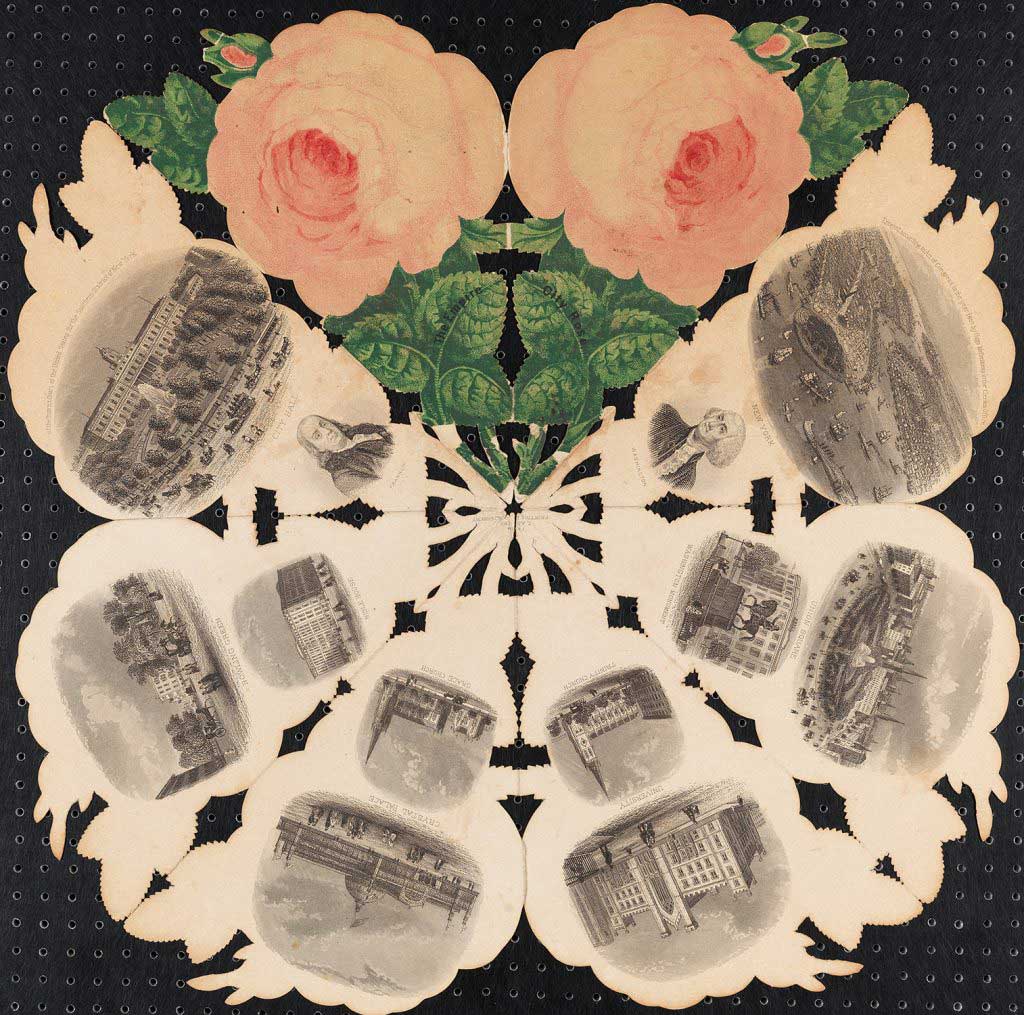

A souvenir cut paper rose depicting historic monuments.

A souvenir cut paper rose depicting historic monuments.

(Image courtesy of Museum City of New York)

A George Washington pitcher

A George Washington pitcher. (Image courtesy of The Chipstone Foundation, Foxpoint, WI)

George Washington and Benjamin Franklin were two favorite subjects for Wedgewood potters in the 1800s. Franklin’s trip to England, when he received the Copley Award for his experiments on lighting and electricity, were honored by Stafford pottery figures.

Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887 offered a variety of commemorative collectibles such as ceramics, woven silk pictures, wallpaper and pipes.

By the middle of the 19th century, important commercial events were happening, creating a growing market for commemorative items. The Crystal Palace’s “Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, London, England” (1851) was the first World’s Fair to exhibit items relating to culture and industry. It included a great diversity of souvenirs, with images ranging from medals to mugs and thimbles.

Not to be outdone, in America, New York City created “The Crystal Palace of Industry Works of All Nations” in 1853. Like the London version, it was made of iron and glass.

Unfortunately, the floor was made of pitch pine. Somehow it caught fire and burned to the ground on Oct. 5, 1858. Currier and Ives created a colorful print depicting firemen fighting the blaze.

The most interesting souvenir is known as “The Rose.” Made of a flat piece of cardboard, it opened again and again in the form of petals, each petal depicting a steel engraving of points of interest. When closed, it was in the form of a colorful full-blown rose. Hundreds were made and printed around the world.

The year 1893 marked the opening of the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The souvenirs depicted images of Christopher Columbus and various exhibition buildings and events.

Chicago’s World’s Fair in 1933 and New York’s World’s Fair in 1964 created many types of souvenirs still available and inexpensive. The Union Pacific exhibit handed out aluminum coins to promote the use of metal in their new trains.

Commemorative items often had a dark side. In Great Britain there was a serious Abolitionist movement beginning in 1783 to end slavery in the United Kingdom and the world. In 1833, an act of Parliament in most British Colonies was passed, freeing more than 800,000 enslaved Africans in the Caribbean, South Africa and Canada.

There were many abolitionists and an Abolitionist Society had created drawing of a black man in chains and the words, “Am I not a man and a brother?” Josiah Wedgwood, England’s most famous potter, convinced his friend, Thomas Clarkson, a member of the Society, to create a medallion that incorporated the image. It became the most famous portrayal of a black person in all of 18th-century art. A medallion was sent to Benjamin Franklin who was then president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. The image was reproduced not only on crockery but fashionable objects from bracelets to being inlaid in gold on snuffboxes. The Wedgwood medallion is and was the most famous image of a black slave in all of 18th-century art.

She has authored nine books on antiques, collectibles, and art and appeared on national TV.

She has done appraisals for museums and private individuals.