Five of a kind: The Dionne Quintuplets

May 2024

SMACK DAB IN THE MIDDLE

Five of a kind: The Dionne Quintuplets

by Donald-Brian Johnson

In the 1930s, Shirley Temple was America’s sweetheart.

Ah, but there was only one Shirley. There were five Dionnes.

Ninety years ago, on May 28, 1934, the Dionne sisters, the first—and so far, only—set of identical quintuplets, were born in Canada. In this day of advanced fertility treatments, multiple births are nothing to get goggle-eyed over. In the 1930s, the odds were one in 57 million. The “five most adorable little girls in the world” made headlines.

Cécile, Marie, Yvonne, Emilie, and Annette Dionne first saw light in a ramshackle farmhouse near Corbeil, Ontario. Their mother, Elzire, had already given birth to six children. She was just 25. Their father, Oliva, with whom the quints had a turbulent relationship, was… well, as he remarked in an early news report, “I’m the kind of fellow they should put in jail.”

The initial survival of the Dionnes was credited to “the country doctor” who delivered them, Dr. Allan Dafoe. The quints weighed in at just 10 pounds, 1-1/4 ounces—total. Dafoe was so uncertain of their fate that he baptized them before the arrival of the parish priest.

Oliva Dionne quickly explored his options. Within three days of their arrival, he’d agreed to exhibit his daughters at the Chicago World’s Fair for $250 a week (plus 23 percent of ticket receipts, if all five lived.)

At that point, the government of Canada stepped in. A court order prohibited Papa Dionne from exposing his daughters to “certain death in some vaudeville show,” and appointed guardians. With their parents sidelined, the Dionnes were on their way to worldwide celebrity.

The “Dafoe Hospital” was built near the family farmhouse. There, the sisters took up residence in a communal crib. As the girls grew, they were photographed constantly, in staged replications of their daily lives: toasting with glasses of milk on their birthday; peering through heart-shaped cutouts on Valentine’s Day: pulling the beard of Dr. “Santa” Dafoe on Christmas. Hollywood came calling, and the quints starred in three films loosely based on their lives, beginning with The Country Doctor in 1936.

And there were the visitors. Each summer brought more than 100,000 guests to “Quintland.” Upon arrival, the curious could view the quints at morning and afternoon “showings” through one-way, soundproof glass. Meanwhile, outside his farmhouse Papa Dionne ran a souvenir stand, complete with personally autographed “fertility stones.”

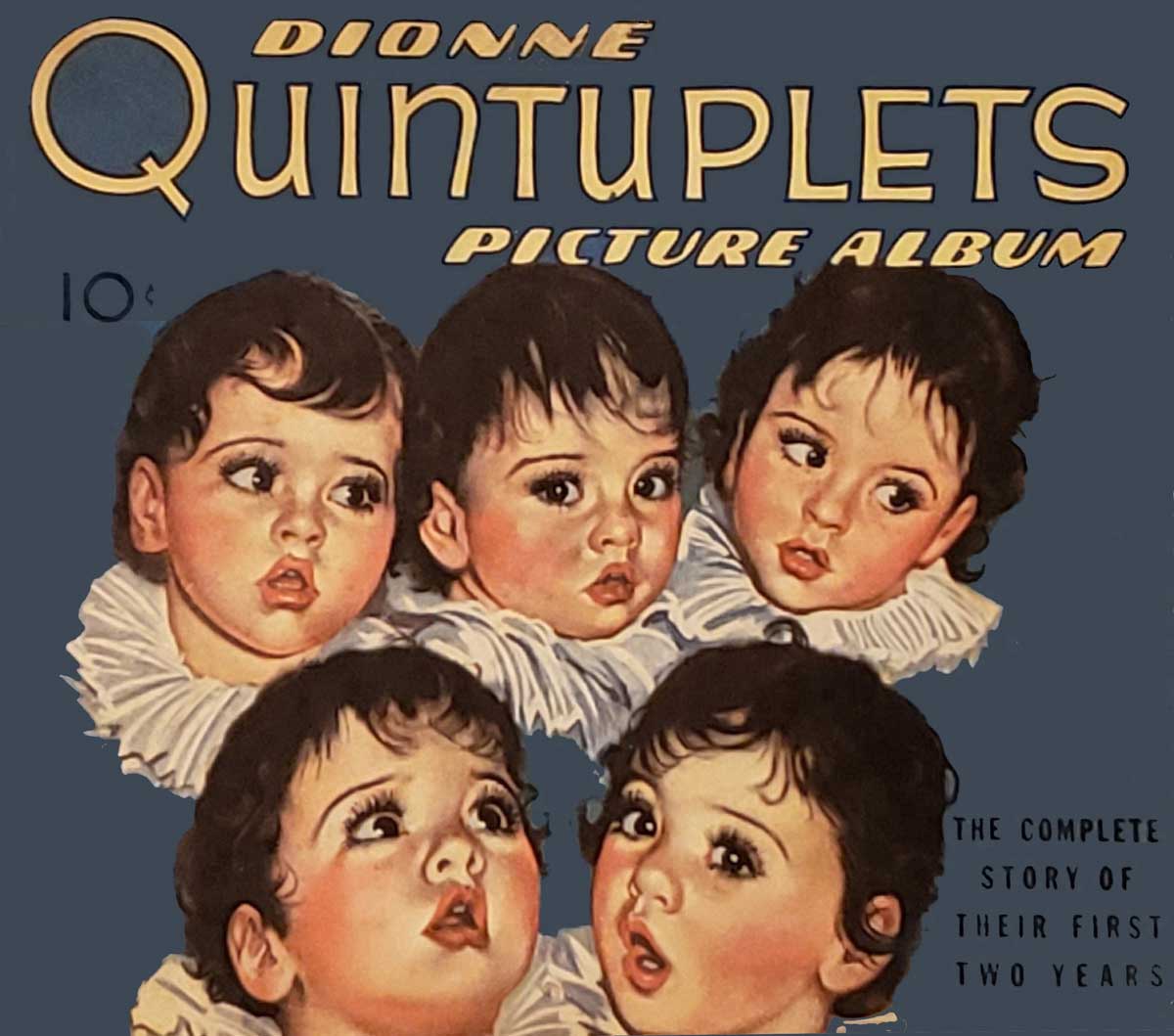

Dionne souvenirs were big business. If you couldn’t afford a trip to Canada, you could at least buy a Dionne hankie, douse yourself with Dionne perfume, wash up with Dionne soaps, or sing along to “Fifty Chubby Tiny Toes—The Quintuplets’ Lullaby.” There were Dionne picture books, Dionne spoons, paper dolls, fans, calendars, games, and dolls. Lots of dolls. The most famous of these, designed by Madame Alexander, jumpstarted her dollmaking career. Advertising endorsements ranged from Karo Syrup to Palmolive Soap. Since so many Dionne collectibles were produced, they remain remarkably affordable. Most sell for well under $50, except for those Madame Alexander dolls, still a pricey $300-plus/set.

The Dionne Quintuplets

Picture books featuring the Dionne Quintuplets were issued at least annually. This one covers “their first two years.” Dionne memorabilia courtesy of Joyce Cramer. (Image courtesy of the author and photography associate Hank Kuhlmann)

Shortly before their 10th birthday, the quints were reunited with the rest of the family. Papa Dionne built a $75,000 mansion, with funds from the girls’ varied endorsements. The reunion was not a happy one. By the time the Dionne Quintuplets turned 20, their “novelty” appeal had largely faded. Following Emilie’s death in 1954 from an unattended epileptic seizure, the sisters became estranged from their parents. Today, only Annette and Cécile survive, and rarely emerge from self-imposed seclusion.

In a 1964 McCall’s article, the sisters wrote, “quintuplets seem to bring out the best and the worst in people.” The Dionnes lived through the worst. The best? The image of youthful joy they conveyed, which cheered a Depression-weary age. As one devotee put it, “the world never ceases to marvel at the phenomenon, and affectionately admire the charming reality of the five most winsome members of its teeming population.”