Old coloring book recalls WWII

June 2023

Vintage Discoveries

Old coloring book recalls WWII

by Ken Weyand

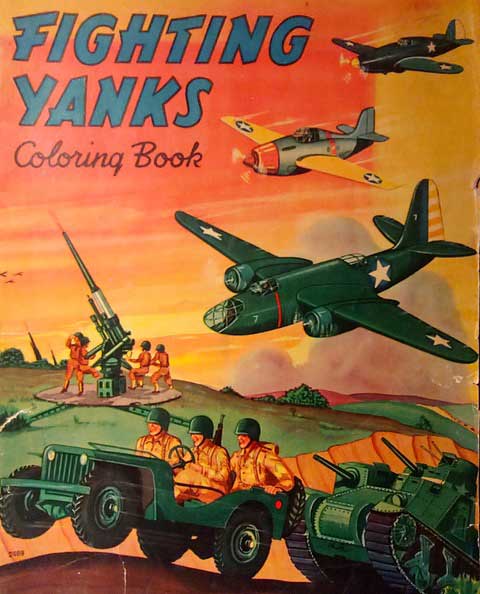

One of the items I’ve saved from my childhood is a coloring book, and its subject matter makes it a bit special. “Fighting Yanks” measures 11 x 14 inches, with a full-color display of warplanes, an anti-aircraft gun, and a Jeep with armed soldiers (smiling and relaxed as if enjoying a Sunday drive), closely followed by a battle tank on the front and back cover. There’s no publishing date listed, but by the book’s content and my coloring “technique,” I’m guessing very early 1940s.

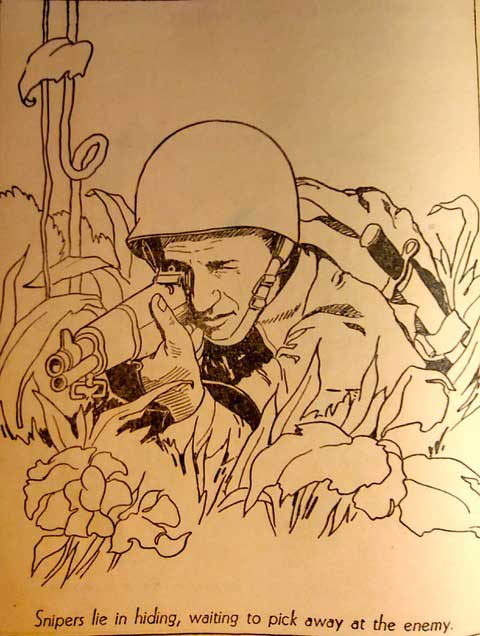

Published by Saalfield Publishing Co., the book contains 64 pages of military-related subjects, printed on newsprint-quality paper. Many wartime activities are included, including Seabees hacking out roads in jungles, trainees practicing hand-to-hand combat with bayonets, workers assembling bombers, an infantryman using a walkie-talkie, snipers, artillerymen, litter-bearers, and more. One page depicts an “American negro soldier on duty in Liberia.”

Several pages depict “home-front heroes,” including a woman working in a hayfield, civilian switchboard operators, a worker recycling tires, and others, including domestic factory workers. Women appear frequently in various roles: home-front workers, USO volunteers, front-line nurses and WAAC’s and WAVE’s performing military duties. Other women are shown supporting their military husbands and boyfriends.

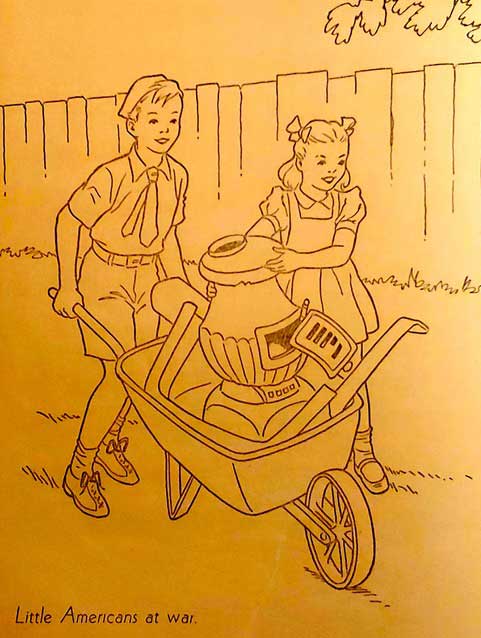

Children are depicted in several ways: buying Savings Bonds, collecting scrap iron for the war effort, pledging allegiance to the flag, and Boy Scouts gathering in a tomato crop to help fill in for farm laborers, a scarcity during the war.

According to Wikipedia, the Saalfield Publishing Company, based in Akron, Ohio, specialized in children’s books and operated from 1900 to 1977. The company published the works of several authors, including Louisa May Alcott, Horatio Alger, P.T. Barnum, Daniel Defoe, Dr. Seuss, Mark Twain, Shirley Temple, and several others.

The company made at least one misstep in 1903 when it published the “New Americanized Encyclopedia Britannica.” It was sued for copyright violation. Wikipedia doesn’t reveal the dollar amount or how the suit was settled.

My copy of the coloring book was not extensively used, and what few pages I colored were not improved by my “artistry.” As a lad of 3 or 4, I obviously had not yet mastered the technique of “coloring within the lines.”

Fighting Yanks coloring book

Ken Weyand is the original owner/publisher of Discover Vintage America, founded in July 1973 under the name of Discover North.

Ken Weyand can be contacted at kweyand1@kc.rr.com Ken is self-publishing a series of non-fiction E-books. Go to www.smashwords.com and enter Ken Weyand in the search box.