Old nursery rhyme book fondly remembered

March 2022

Vintage Discoveries

Old nursery rhyme book fondly remembered

~ by Ken Weyand ~

My first books

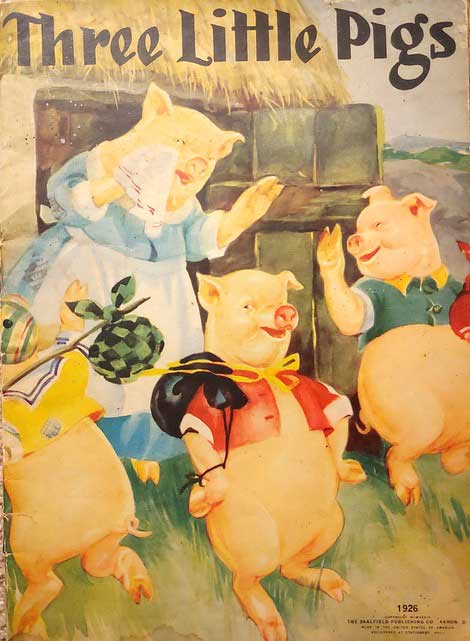

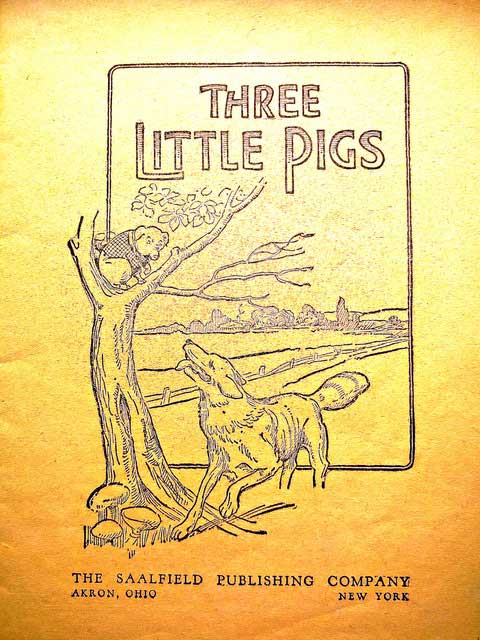

One of my first books – saved by my mother over the years – recently turned up in my attic. “Three Little Pigs” is a nursery rhyme classic, and it was fun to rediscover this gem many decades later.

My book contains four nursery rhymes. Besides the pigs’ saga, there is “Puss In Boots, Cinderella,” and “Hansel and Gretel.” Like most books of its type, this one features large type and detailed line drawings: 64 pages of black & white newsprint within a colorful cover.

The book was one of many produced by the Saalfield Publishing Co. of Akron, OH. According to a 2014 article in the Akron Beacon Journal, the company’s fortunes as a publisher of children’s books took a giant leap in 1902 when a Chicago housewife, Francis Montgomery, submitted a first manuscript, “Billy Whiskers: an Autobiography of a Goat.” The book (along with follow-up versions) was a stunning success, and the company went on to become the largest publisher of children’s books in the world.

Reading “Three Little Pigs” and the other stories in today’s era of political correctness reveals how far the genre has come. All the stories contain various forms of violence: the wolf ate two of the three pigs, and the third pig “had the wolf for supper.” “Hansel and Gretel” depicts abandoned children who save themselves from a cannibalistic witch when Gretel shoves the old lady in a blazing oven. Nice.

In the early 1940s, when I began my studies at Black Oak, a country school a half-mile from our Missouri farm, I was treated to the “Dick and Jane” books. The urban family of Dick, Jane, Baby Sally, their pets and straight-arrow parents was depicted with syrupy sentences, usually of fewer than a half-dozen words. Although my classmates probably enjoyed them, I thought the simplistic “Dick and Jane” stories were incredibly boring.

Compared to the mayhem and violence I’d discovered in the “Three Little Pigs,” maybe they were.

Three Little Pigs

“Three Little Pigs” book cover. (photos by Ken Weyand)

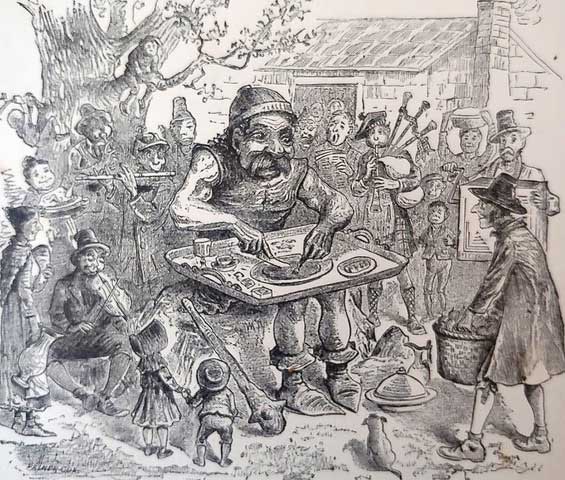

inside art of Three Little Pigs

Sample page from “Three Little Pigs” book showing artwork.

back cover Three Little Pigs

Back of book; published by The S.A. Alfield Publishing Co.,

Akron, OH and New York, NY, 1926.