Flying ‘back in time’ in a vintage biplane

~ October 2018 / Traveling with Ken ~

Vintage Discoveries

Flying ‘back in time’ in a vintage biplane

~ by Ken Weyand ~

Flying in an open-cockpit biplane is a forgotten part of our history. It was an era when pilots flew “tail-dragger” aircraft from grass strips and navigated by following railroads and section lines. One company near Excelsior Springs, MO, helps you experience it again.

Outlaw Aviation ? more conservative and law-abiding than its name implies ? lets clients roar through Midwest skies in a vintage biplane. Its aircraft is a Stearman ? officially a PT-17 Boeing Super Stearman ? a derivative of the model used as a Navy trainer before and during World War II.

At war’s end, many of the aircraft were auctioned, beginning new careers as crop dusters, transportation for movie stars, or toys for wealthy eccentrics. Others went to air shows as aerobatic performers. Moviegoers saw a Stearman, converted to a crop duster, attacking Cary Grant in the 1959 Alfred Hitchcock movie, North By Northwest.

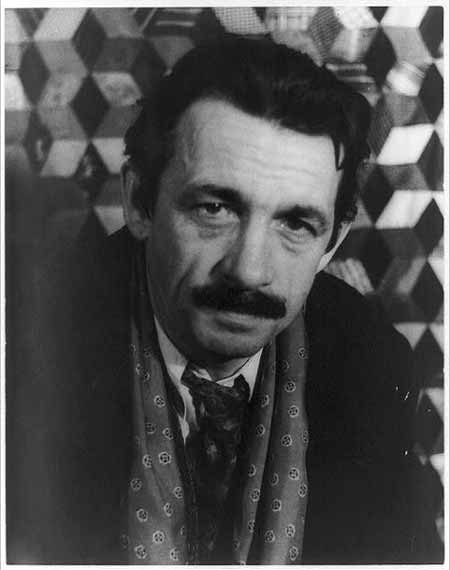

Lee Crouch, owner of Outlaw Aviation, offers rides in the Stearman, with rates for one or two persons. However, only one passenger at a time can be accommodated in the two-place biplane. Crouch is one of only a few entrepreneurs who offer that kind of service. Crouch soloed at age 16. He has nearly 30 years of aviation experience under his belt, having been an Alaskan bush pilot, as well as a captain for a major jet operator. Since he began offering Stearman rides 10 years ago, Crouch has helped more than 500 people experience open-cockpit flying.

Outlaw Aviation’s “Super Stearman” ready to fly (Ken Weyand photo)

Crouch’s biplane, built in 1941, differs from the original Navy trainer in several ways. “Basically it’s got a more powerful engine,” Crouch said. “It was built by Boeing after the company took over the original Stearman operation in Wichita.” Crouch said Boeing built 13,000 airplanes, with 7,000 used for training and 6,000 for spares. “My biplane trained pilots in Texas, then became a crop duster between 1996 and 2001. Later, more than 7,000 man-hours went into restoring and updating the aircraft.” Modifications improved the biplane’s aerodynamic qualities.

Crouch said the Stearman is ideal for air shows. In addition to giving 20-minute rides, his company offers an “old school barnstorming smoke and noise air show,” and calls the Stearman “the ultimate air show machine.”

Crouch said most rides are purchased as Christmas gifts ? usually redeemed in the spring, but also are given throughout the year. “It’s the ultimate gift for any aviation enthusiast,” he said. “I tailor the ride to the individual, and the whole family is invited to come to the airport, take photographs, and watch the flight.” For details, visit www.flyoutlaw.com.

The Stearman in flight (Outlaw Aviation photo)

A reporter takes a flight

My daughter, Holly, and her friend Sean, gave me an Outlaw Aviation flight for my birthday several months ago. Other things got in the way, including the summer heat wave, and I decided to take the flight in early September. I made the appointment, and drove to Midwest National Air Center, an airport near Mosby, northeast of Kansas City.

Lee Crouch and the Stearman soon appeared on the tarmac. After taking care of the necessary paperwork, Lee and I walked to the biplane and he gave me a short briefing. My “floppy hat” and sunglasses weren’t suitable for the flight, and I opted for a pair of flying goggles and a leather safety helmet. Then it was time to board.

“This is the most dangerous part of the flight,” Crouch said, as he showed me the part of the wing that served as a step, and the handholds on the upper wing center section. The procedure was simple: stand on the “step area,” grab the handholds, lift your right leg above the cockpit and onto the seat, then pull yourself to an upright position using the hand-holds, and lower yourself into the seat. “Take your time,” he said. I entered the cockpit with no problems.

He secured me in the cockpit with safety harness, told me where to place my feet (out of the way of the rudder pedals and joystick) fitted me with a pair of headphones, and advised me about the push-to-talk feature on the attached microphone. “It gets a bit noisy,” he said.

Stearman trainers in flight at NAS Flight School, Pensacola, FL, 1936 (U.S. Navy photo, courtesy Wikipedia)

He started the Stearman’s mighty 450-hp engine, taxied to the end of the runway, and warmed up the engine. When he applied power, we roared down the asphalt strip, and were quickly airborne.

Although I had been a pilot in the 1960s and ’70s, my flights in small trainers and other private aircraft didn’t offer the excitement of the open-cockpit Stearman with its burly power. The air was a little bumpy, but Lee handled the controls smoothly, and we took a low-level tour of rural Clay County north of the river, including a brief pass over a small airstrip. Then we headed toward the Missouri River and Lee dipped the wings to let me scout a kayaking location I had requested to spot from the air.

Our flight was comparatively “straight and level,” but at one point Lee executed a smooth barrel roll, giving me a taste of inverted flight. It was an added bonus, although I hadn’t chosen an available aerobatics upgrade. “This plane really likes to fly inverted,” he told me later.

Then we approached the field, flew a short base-leg and touched down on the runway. When I exited the plane, it felt like a natural process. My “biplane experience” had been exhilarating.

Ken Weyand can be contacted at kweyand1@kc.rr.com Ken is self-publishing a series of non-fiction E-books. Go to www.smashwords.com and enter Ken Weyand in the search box.