~ July 2017 / Traveling with Ken ~

Vintage Discoveries

Thomas Hart Benton home preserves painter’s spirit

~ by Ken Weyand ~

The Thomas Hart Benton Home and Studio State Historic Site at 3616 Belleview in Kansas City, MO, looks as if the artist might walk in and resume working at any moment. The site, just west of Summit Street in the Roanoke neighborhood, preserves the house and studio where the artist spent most of his controversial career.

Detail from Archelous and Hercules, a 1947 mural for Harzfeld’s department store in Kansas City, donated to the Smithsonian when the store closed in the 1980s (courtesy Wikipedia)

In the early 1940s, shortly after he and his family moved in, Benton converted the carriage house into a studio, installing a large window on the north side for the best light. Coffee cans are full of brushes, and jars of paint appear ready to be applied to a stretched canvas.

On Jan. 19, 1975, Benton died while finishing a mural for the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville. He was 85.

Benton’s life and times

Benton was born April 15, 1889 in Neosho, MO. The family was already established in Missouri politics. Tom’s great-great-uncle, the “other” Thomas Hart Benton, was one of the state’s original senators. Tom’s father, a four-time U.S. Congressman, wanted his son to continue the family’s political heritage, and enrolled him in Western Military Academy in Alton, IL.

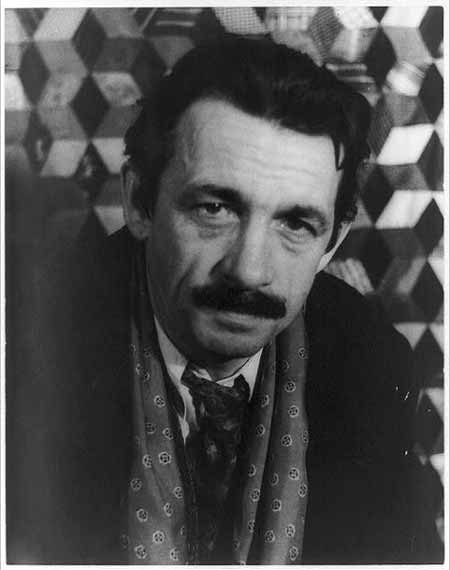

Benton in 1935 (photo by Carl Von Vechton, courtesy Wikipedia)

But Tom, a budding artist, rebelled. As a small child he gaped in awe at the great murals at the Library of Congress when the family lived in Washington, D.C., and he loved to draw. In 1906, he worked briefly as a cartoonist for the short-lived Joplin American newspaper.

Unlike his father, Tom’s mother supported her son’s creativity, and in 1907 she enrolled him in

the Chicago Art Institute. Two years later, with her support, he moved to Paris and enrolled in the Acad?mie Julian. In 1912 he moved to New York City to begin painting full time. He spent summer months painting at Martha’s Vineyard, MA.

Benton served in the U.S. Navy during World War I, and was put to work making illustrations of shipyard workers. He also worked as a “camofleur,” drawing camouflaged ships in Norfolk harbor. His artwork helped painters apply camouflage and later helped identify ships that were lost at sea. Returning to New York in 1920, Benton spurned modernism and embraced a naturalistic style now known as Regionalism. He became active in leftist politics, and his murals often included controversial subjects such as the Ku Klux Klan, which stirred criticism when Benton included them in a mural for the 1933 Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago.

But Benton persevered, and in the mid-’30s his Regionalism style began to be recognized as a significant art movement. Still, he was at odds with many critics and “art elites” for his politics and “folksy style.” Tired of the controversy, Benton returned to Missouri, where he was commissioned to paint a mural for the State Capitol. Titled “A Social History of Missouri”, it is considered by many to be Benton’s best work.

Studio area puts visitors in Benton’s world (photo by Ken Weyand)

Benton in Kansas City

In 1935, Benton moved to Kansas City and began working as a teacher for the Kansas City Art Institute. Close to rural America, he painted farm scenes in his bold and colorful style, concentrating on farm families struggling to survive the Depression years.

During this period he created his most controversial painting, “Persephone”, featuring a reclining nude being ogled by a grizzled farmer. Benton called it allegorical; the Art Institute called it scandalous. Today, it is exhibited at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. The painting began a rift with the Art Institute that came to a head in 1941 when Benton called art museums “a graveyard run by a pretty boy with delicate wrists and a swing to his gait.” It was the last straw for the Art Institute, and Benton was dismissed.

Benton continued to paint during World War II, creating a series of prints entitled “The Year of Peril,” depicting threats by fascism and Nazism that were widely distributed. He also produced several important murals, including “Lincoln” for Lincoln University in Jefferson City, MO, “Trading at Westport Landing” for The River Club in Kansas City, “Father Hennepin at Niagara Falls” for the Power Authority of the State of New York, “Joplin at the Turn of the Century” for Joplin, MO, and “Independence and Opening of the West” for the Truman Library in Independence.

The Benton house

Benton home, in KC’s Roanoke area (photo by Ken Weyand)

Katie Hastert, site interpreter, gave me a tour, beginning at Benton’s studio in the carriage house. The north window is the only light source; all other windows were covered. “Most items are just as they were,” she said, “except the easel is turned a bit, since it faced the north window when Benton painted. Visitors kept asking what was on it, so we turned it around.”

Katie Hastert, site interpreter, with original bar items, and 1922 self-portrait of Benton and his wife, Rita (photo by Ken Weyand)

Benton made sketches of his subjects before painting them, and examples are here. There is also a “maquette,” a three-dimensional clay model Benton made before starting work.

“Benton believed in common art for the common man,” Hastert said. “He considered murals the highest form of art, since ordinary people would see them. Otherwise, he preferred barrooms to galleries.”

Rooms in the main house remain as they were when the Bentons lived here, with Tom’s pipe on an ashtray, bourbon bottles in the bar, and hundreds of books in the large bookcases. All furnishings are original.

“The house was built in 1903,” Katie said. “It cost $38,500 to build. The Benton’s paid $6,000 for it in 1939.”

For hours and more info, call 816-931-5722 or visit https://mostateparks.com/park/thomas-hart-benton-home-and-studio-state-historic-site.

Ken Weyand can be contacted at kweyand1@kc.rr.com Ken is self-publishing a series of non-fiction E-books. Go to www.smashwords.com and enter Ken Weyand in the search box.